Advertising of the past is embarrassing. The present's is too, but it has filters

- Fotoprostudio

- Aug 28, 2025

- 10 min read

The advertising of the 20th century leaves us with an uncomfortable lesson: what seemed normal was, in fact, violent, racist, classist, or cruel. Yet, it sold. Today, we are scandalized by those mistakes. But what if we are repeating them, just with different colors, new technology, and fewer excuses?

This article isn't merely a critical look at the past. It is a warning about the present: many of those same logics haven't disappeared; they've simply been updated with Instagram filters, progressive euphemisms, or TikTok aesthetics. Retro isn't always innocent. And nostalgia can be a dangerous form of amnesia.

Índice

1. Cigarettes for everyone

In the 1950s and 60s, brands like Camel, Lucky Strike, and Chesterfield normalized tobacco consumption not only among adults but also within the children's imagination. Some advertisements directly featured images of children to reinforce the idea that smoking was natural, everyday, and socially accepted. In others, children appeared as accomplices or admiring spectators of adult smokers. For most consumers of that time, there was no clear awareness of the real effects of tobacco: information about respiratory diseases, addiction, or cancer was scarce, and in many cases, even denied by the medical industry. Smoking wasn’t seen as a dangerous habit; it was a symbol of belonging, maturity, and an aspirational lifestyle.

Old Tobacco Advertising vs. Today's Tobacco Advertising

Current Analogy: Today, no advertisement would dare show a minor smoking, yet on platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram, adolescent influencers are promoting vaping devices, disposable vapes, flavored options, and products with colorful packaging and pop aesthetics. These products are marketed as "healthier alternatives" to tobacco, despite uncertain scientific backing, poor regulation, and largely unstudied risks. Just like in the past, popularity is being confused with safety.

Numerous brands are being promoted by influencers under 25 in videos that accumulate millions of views, without visible health warnings or objective information. Vaping today is what cigarettes were in the 1950s: an aspirational trend disguised as a harmless habit. The result, much like before, will be borne by an entire generation, with highly stylized content aimed indirectly at minors.

Happy, thin, and sedated: Yesterday it was them, today it’s everyone

From the 1950s to the 1970s, advertising aimed at women assumed their role was tied to the home, beauty, and emotional obedience. But if that formula didn’t work, if the woman felt anxious, dissatisfied, or simply tired, the solution was not to review the social model, but to medicate her or sell her something to keep her functional and thin. Pills to calm nerves, tonics to energize the body, alcohol to better handle the load. A Spanish example is the Fundador brandy ad, where a smiling woman served her husband a drink as a symbol of marital balance. Alcohol was a silent, socially accepted aid, with its risks made invisible.

Advertising for Tranquilizers with Vitamins vs. Advertising for Vitamin Supplements

Current Analogy:

Today, wellness discourses have changed their packaging, but not their essence. On social media, especially among young women, there is an explosion of supplement recommendations that promise to calm, balance, or transform the body and mind. Magnesium drops for sleep, collagen for self-esteem, adaptogens for stress. There's no diagnosis, but there is a promise. There's no warning, but there is a hashtag. And if it doesn’t work, the blame is yours for not doing “enough.”

Influencers promoting products like Altrient C, melatonin, or ashwagandha with phrases like "this changed my life," without mentioning possible side effects, interactions, or lack of clinical backing. Meanwhile, the recreational use of drugs like Ozempic or Saxenda continues to rise among women who don’t need them but seek to fit into a visual mold. Among men, the use of non-prescribed hormonal supplements or anxiolytics is also growing to maintain an image of success. Like in the 60s, we continue to silence discomfort... through consumption. In Spain, brands like Altrient or Ana María Lajusticia have been promoted by influencers on Instagram under the umbrella of emotional well-being or female energy, without clarifying the commercial nature or possible side effects. Social media is filled with reels selling "self-care routines" that are, in fact, undercover marketing for supplements, detox shakes, off-label drugs, or weight loss products. The pressure remains: women must be happy, thin, and have perfect skin. Only now, it’s sold as "empowerment."

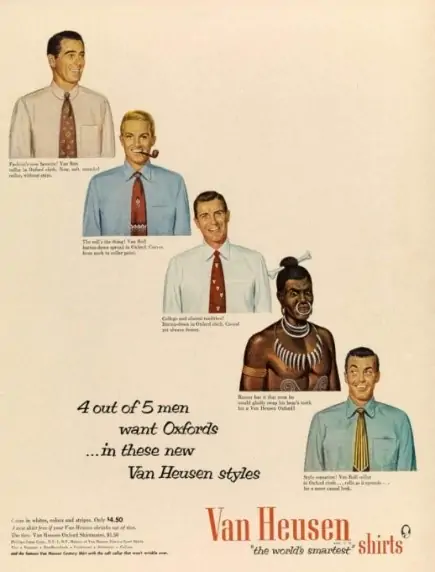

3. Visual racism as a marketing tool

For decades, advertising used racial stereotypes as an aesthetic formula to capture the attention of the Western white consumer. Black people were depicted as smiling servants, Asians as obedient or enigmatic caricatures, and Indigenous or Arab cultures as voiceless exotic figures. They did this with impunity and a festive aesthetic, as if there was nothing offensive in reducing an identity to a costume. What was actually symbolic domination became marketing. And the audience didn't question it, because it was designed not to see it.

Van Heusen Shirt Advertising vs. African Fashion Advertising

Current Analogy: Visual racism has not disappeared. It has only learned to dress itself in inclusion. Many current brands use racialized bodies as exotic backdrops or tools of visual political correctness, while still failing to represent them in decision-making roles or in real messages of power. Diversity becomes decoration, not substance.

Example: Fashion campaigns that place Afro-descendant models in landscapes that evoke poverty or tribalism, without context or history. Or when they appropriate aesthetics like Afro hair or Asian iconography without giving credit, paying in visibility but not in rights. As before, the image of the "other" is used to construct the desire of the dominant. Also, when brands directly whiten models in post-production to make them "more marketable."

4. Alcohol as medicine: Gin, whiskey, and champagne at breakfast

From the 1950s to the 1970s, advertising promoted alcohol consumption as a solution for various everyday situations. Gins, whiskeys, and digestive liqueurs were presented as balms for stress, sadness, or even morning fatigue. Ads from brands like Johnnie Walker, Terry, or Anís del Mono suggested that a single glass could transform a mediocre day into a sophisticated and happy experience. What is most troubling is that, at that time, the average consumer was not fully aware of the long-term effects of alcohol: information about addiction, liver damage, or emotional dependency was scarce or nonexistent in popular discourse. Drinking was a social custom, not a risk.

Fundador Brandy Advertising vs. Current CBD Dropper Advertising

Current Analogy: Today, something similar is happening with the boom of "natural" supplements. From capsules for sleep to drops for mental focus, thousands of products are promoted daily without solid scientific evidence and without clear warnings about their medium- or long-term effects. Just as with alcohol decades ago, the advertising language, now in the hands of influencers, turns these products into seemingly harmless acts of self-care. However, many contain active ingredients with unstudied interactions, excessive dosages, or unfounded promises.

The use of ashwagandha, melatonin, CBD oil droppers, or adaptogens like reishi is on the rise, promoted by wellness profiles that mix emotional testimonials with recommendations lacking professional backing. Few consumers read the studies, and even fewer consult with doctors. Just like with alcohol in the past, what is socially accepted is often confused with what is medically safe.

5. Use children: No moral filter, then or now

In the 20th century, advertising frequently used the image of children to promote products, even those unsuitable for minors. It was not uncommon to see children advertising cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, or highly toxic cleaning products. They appealed to their innocence or cuteness to reinforce the idea that the product was trustworthy. The most alarming thing is that the general public was not aware of the real risks associated with those products: no one talked about toxicity, addiction, or long-term consequences. It was assumed that if it appeared in an ad, it must be safe.

Old Nocilla Advertisement vs. Influencer Ibai Llanos Sponsoring Donettes

Current Analogy: Today, many child influencers have millions of followers on platforms like YouTube, Instagram, or TikTok. Through their channels, they promote everything from sugary snacks to electronic devices, with little to no real oversight regarding what they are endorsing or the potential consequences. Many of these products, such as energy drinks, gambling apps disguised as games, or cosmetic items, can have negative effects on the physical and psychological development of minors.

As in the past, the audience (in this case, other minors) trusts the image more than the evidence. There is little awareness of what lies behind the scenes: brand contracts, scripts, lack of regulation. The pattern repeats itself: the visual overshadows the ethical. The "adorable" sells, even if the price is paid by the most vulnerable.

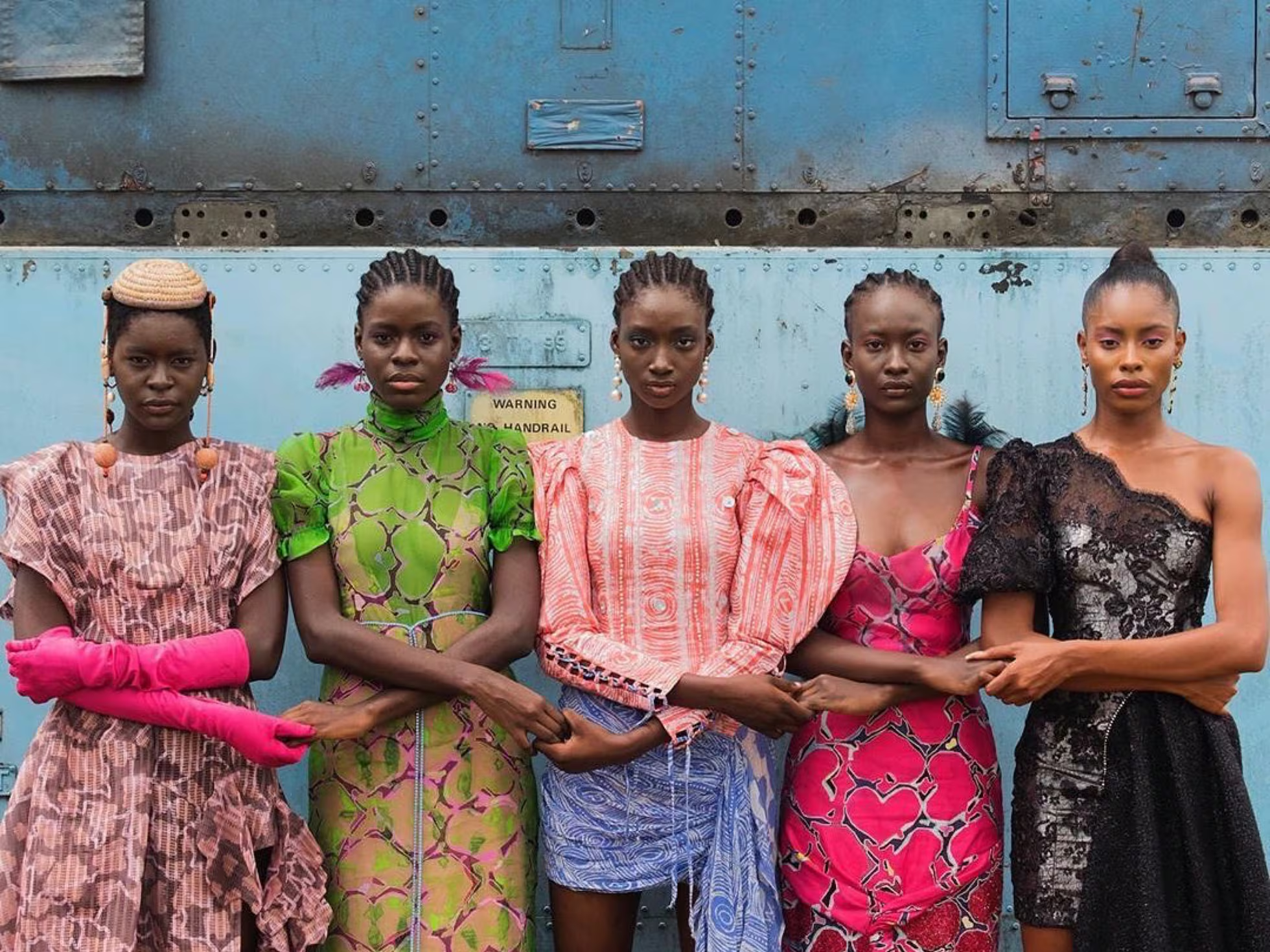

6. From the apron to the likes

For much of the 20th century, advertising built an image of women as helpful, silent, and grateful. She was the wife who served with a smile, the secretary who accepted sexual compliments as part of her emotional salary, the mother who had to worry about not leaving stains on her clothes... and on her reputation. The apron was her uniform, and silence was her motto. What was disturbing was not only the message, but how accepted it was: she was expected to be happy with little, beautiful without effort, and docile without protest.

Budweiser Beer Advertisement vs. Current Fashion Advertisement

Current Analogy: Today, the apron has become a set of gold hoops, natural light, and a kitchen with white marble. The feminine ideal still circulates strongly, but it has migrated to screens. Social media, especially Instagram and TikTok, are filled with profiles of women who, under the guise of wellness, perpetuate the same mandates of the past: be beautiful, be kind, don’t complain, create content. The algorithm rewards performative femininity—one that doesn't make waves, one that decorates.

What was once printed in magazines is now filtered and monetized. Yet the logic remains unchanged: if you don’t fit in, you don’t sell. Influencers and advertising campaigns continue to present beauty and behavior ideals that pressure women to conform to unrealistic standards. Additionally, targeted advertising on social media can increase the mental load on women, especially when it taps into their insecurities about health, appearance, and family roles.

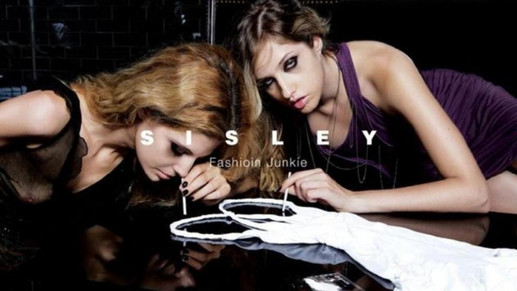

7. When the scandal doesn’t kill, it multiplies

In the 80s and 90s, some brands discovered that provoking was profitable. The strategy was not to avoid controversy, but to design it. Benetton shocked the world with images of a dying AIDS patient, a kiss between a priest and a nun, or a newborn baby covered in blood. Calvin Klein crossed the boundaries of legality by showing teenagers in underwear in settings resembling clandestine auditions. These campaigns did spark outrage, yes. But they also achieved what they set out to do: global visibility, free media coverage, and a “brave” brand image. Controversy became capital.

Benetton’s AIDS Patient Advertisement vs. Current Sisley Advertisement

Current Analogy:In today’s digital ecosystem, many brands still use scandal as currency. They release campaigns that are ambiguous enough to spark controversy, knowing that outrage spreads faster than applause. Then comes the apology—measured and calculated. The cycle repeats: impact, virality, retraction, forgetfulness. And sales.

Example:Balenciaga was accused of sexualizing childhood in a visual campaign many deemed unacceptable. The brand removed the images, apologized, and… moved on. Their notoriety increased, mentions skyrocketed, and public conversation centered around them for weeks.

Another case: Shein, embroiled in accusations of plagiarism, greenwashing, and labor exploitation, continues to lead global sales thanks to its aggressive daily microtrend strategy. Noise is not always punishment. Sometimes, it’s just part of the plan. In the digital age, some brands have faced criticism for campaigns considered insensitive or inappropriate. However, many have opted for rebranding strategies or public apologies to mitigate the negative impact and maintain their market presence.

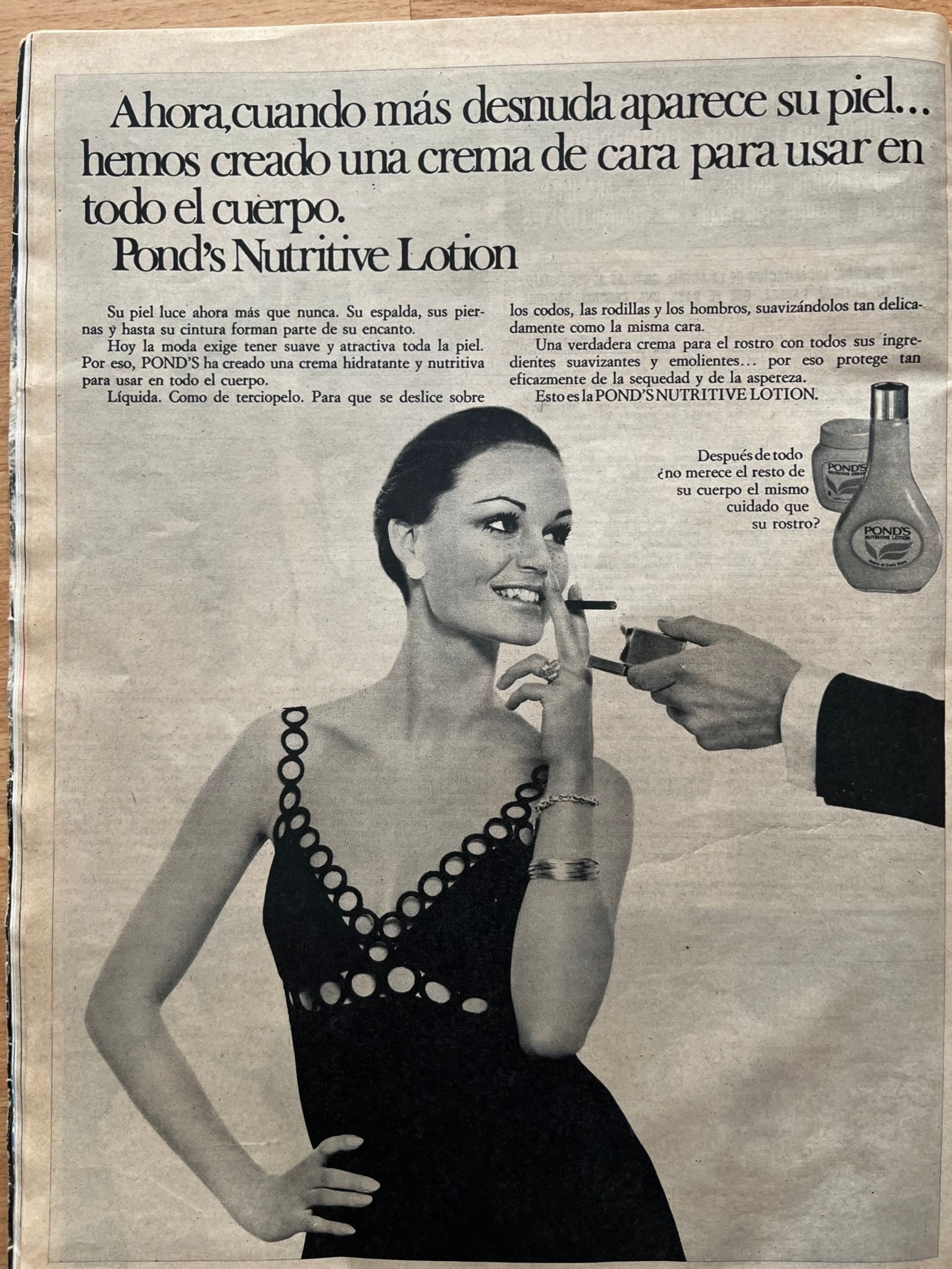

8. Beauty as punishment

Throughout much of the 20th century, advertising turned the female body into a battleground. The ideal was clear: white skin, extreme thinness, perpetual youth. Creams to lighten skin, amphetamine pills for weight loss, and corsets promising "wasp waists" in weeks were sold. Health, autonomy, and diversity didn’t matter. All that mattered was fitting in. And if that meant lightening the skin or doping oneself, it was part of the price to belong to the display of what was considered acceptable.

Old Advertisement for Body Creams vs. Current Advertisement for Depigmenting Cream

Current Analogy:Today, the packaging has changed, but not the mandate. Cosmetic surgeries, beautifying filters, miracle supplements, and hyper-produced aesthetics are presented as free choices. But true freedom demands options, and the system still rewards the normative: clear skin, defined cheekbones, a minimal waist, no wrinkles.

On TikTok, teenagers use filters that refine their faces in real time. On Instagram, the edits are so subtle they seem natural, and that’s what makes them more dangerous. The body ideal has gone digital… but it’s still exclusive.

Whitening creams are still sold in many countries, but now under gentler names like “tone unifier” or “glow effect.” What used to be a direct imposition is now disguised as a personal choice. But it still hurts the same. Instagram filters, cosmetic surgery, and products without scientific backing saturate the feed. The perfection ideal is repeated as an obligation, now disguised as a free choice. What is sold as neutral aesthetics still responds to colonial or classist hierarchies.

9. When advertising remains silent

Advertising didn’t just sell products: it sold edited versions of reality. It promised a colorful future while the streets were still in black and white. It was a mirror of its time, yes, but also a curtain: it hid more than it revealed.

Current Analogy:Today, campaigns show diversity, sustainability, or social commitment, but often only on the surface. They show just enough to appear as though a lot is being done. "Eco" brands that celebrate International Women's Day while firing pregnant women. Companies that advertise “green” products made under precarious conditions. The narrative has changed, but the logic remains the same: show what sells, hide what compromises. Behind visual inclusion, there’s often a lack of real structural justice. Eco aesthetics without real sustainable practices.

Conclusion

We look at the ads of the past and we are scandalized. We laugh at their naivety, their audacity, their cruelty disguised as normality. We think, "How didn’t they realize?"

We point out the mistakes of another era with arrogance and superiority, but we are replicating many of them... with better graphics, better slogans, and algorithms that filter everything so it doesn’t hurt.

We live in constant advertising, connected 24/7/365. Everything is marketable. Everything has an aesthetic. Everything is a message. But the most unsettling thing is not that we’re surrounded by stimuli: it’s that we no longer perceive them as such. Advertising doesn’t just interrupt our lives; it structures them.

It’s in the bodies we idealize, in the discourses we repeat, in the habits we adopt without questioning. We’ve internalized its logics until we confuse them with common sense.

The future will scrutinize us, as we scrutinize the past. And maybe they won’t call us idiots. Maybe they’ll say something worse: that we knew. That we saw it. That we had all the data. And still, we clicked the heart. We shared. We bought. We stayed silent.

Comments